So, what is ‘good’ co-design?

What is co-design?

Co-design is quite topical in the health and social services sectors and there can be some confusion about what co-design is, and probably more so what it isn’t and what is involved in a true co-design process.

Actually breaking down the word ‘co-design’ can help to develop a clear understanding of what it is. Co-design, derived from:

Co - which has been extracted from collaborate, collective and consultative and,

Design - which refers to an intentional process used to develop solutions, innovations or improvements that address problems and open up possibilities for better outcomes.

In a nutshell, co-design is purposefully collaborating with people - which we call a co-design team - to identify and understand what the problems are. It’s then continuing to work collaboratively with those same people to develop solutions to those problems they have identified and then, again, working with those same people to test the implementation of those solutions. And at the core/heart of that co-design process is improving consumer outcomes and experiences.

What can make co-design tricky and a bit challenging to define is that there isn’t a definitive structure or universally accepted best practice approach. Rather there are recognised principles and elements which should underpin any co-design process. And we will cover those in future blogs.

Although there isn't a best practice approach, there are several frameworks underpinned by recognised principles that are available to guide you in implementing your co-design efforts and again we will go through several of those in future blogs.

What is ‘good’ co-design?

So we know co-design is collaborating with people to understand problems and develop solutions and then test those solutions, but what does ‘good co-design’ look like in practice?

You need to consider who is involved

To do co-design effectively, we must work alongside a diverse group of people (that co-design team I mentioned before) to ensure the solutions that are developed - whether that be a service or a program, reflects the needs, values and goals of the people that it’s intended to serve. Any co-design team should and really must include consumers, including people with lived experience, health professionals and other professionals who deliver the service. It may also include clinical leaders and representatives from commissioning organisations, government and non-government organisations. The makeup of your co-design team will really be informed by the topic area and scale of the project or problem that you are trying to address.

You need to adapt the process

Good co-design also means adapting how we engage that co-design team based on the project context. So the principles we use to engage them will be the same but the process itself might and really should look different depending on the subject matter, the target population(s), the project timeframe and also the broader program/service and political context. For example, the process of co-designing a program to increase health literacy among culturally and linguistically diverse communities in a single local government area in QLD is going to be different to the process for developing a model of care to address an increase in acute mental health presentations across an entire HHS catchment. How you engage people (the methods and resources you might use), and how you support participants in the co-design process is going to be different to support good outputs.

You need to keep people engaged

So we’ve talked so far about the process of co-design - from defining what the problem or problems are, to developing solutions to those problems, right through to testing and piloting those solutions for implementation. Good co-design involves engaging the co-design team in that entire process. Importantly, we aren’t going into the co-design process with preconceived ideas about what the problems are that people face and what the solutions should be. We also aren't asking people what the problems are so that we can then go away and develop those solutions independently. It can’t be emphasised enough here that it is the co-design participants who are the decision-makers but that is done and led in a structured and facilitated way.

You need to think broadly

Lastly, a good co-design process also considers the broader evidence base and brings this together with people’s experiences. It is still important to review and understand the evidence on what works well, what doesn’t work well, what is best practice, and also what is happening more broadly in the external/political environment. Having a broad understanding of the emerging policy and practice implications that might impact the project is foundational to developing appropriate solutions. This is important when facilitating any co-design process to ensure we have knowledge of the project context and can facilitate the development of fit for purpose solutions by the co-design team. For example, at Beacon Strategies, when we undertake a co-design project, our first step usually involves undertaking desktop research. We might look at the policy landscape, and the service delivery history both locally and elsewhere so that we can understand what service models have been operationalised and worked well in other areas, and identify or pre-empt what some of the gaps or challenges might be. The point of co-design isn’t to reinvent the wheel. So just to emphasise here the importance of engaging with the co-design team to hear from them about their perspectives and experiences, but also the need to overlay this with the broader evidence base.

What co-design isn’t...

As I mentioned earlier, co-design is being referred to and discussed more and more in the health and social services sectors. With this, sometimes things are might be labelled co-design when they are probably more aligned with an engagement or consultation design approach.

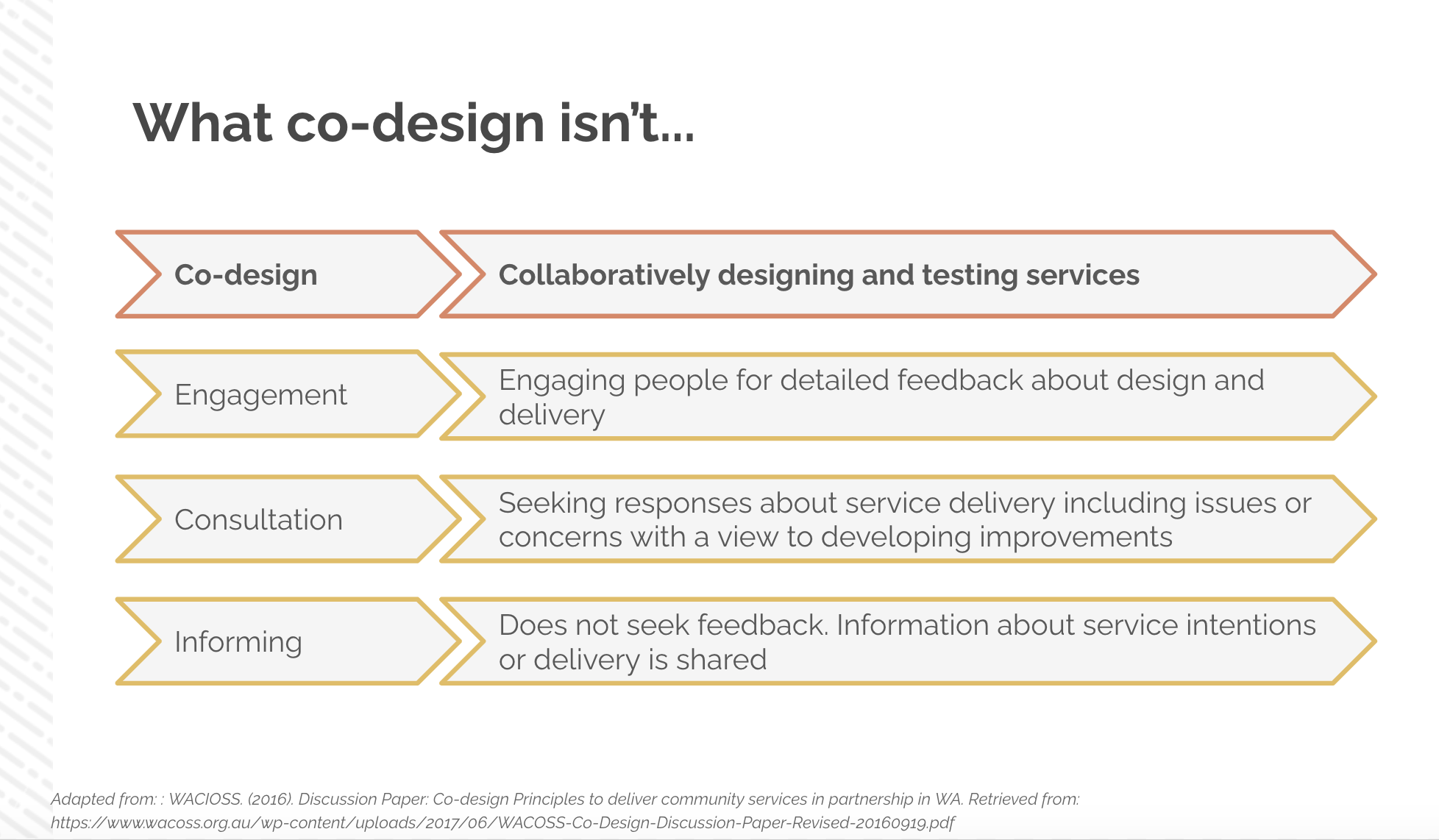

It is important here to highlight the difference between engagement, consultation and co-design. This graphic has been adapted from a great resource produced in Western Australia and it demonstrates in a simple and really clear way the different levels of design.

Informing: when we are informing, we tell people this is what we intend to do...and we aren't asking for feedback on that.

Consultation: we are asking people to share their knowledge and perspectives on a topic including what their issues and concerns are. But we then take that information or insight away and develop our own solutions to those issues

Engagement: Goes a bit beyond consultation and asks people for feedback about the design and delivery of a program/service

Co-design: goes further still and aims to develop a really deep understanding of an issue and co-decide on solutions rather than seek feedback. In consultation or engagement, we might talk with a lot of people, but in co-design, our team might only consist of 6-8 people because we are a prioritising depth in our understanding of the problems people experience and are focussing on collecting robust insights as opposed to going wide in our engagement with people.

One other key difference is that you may have noticed that we talk about co-design being a process and that’s because it isn’t a single event or once-off engagement with people. Co-design can take months and is often iterative in nature.

Just to be clear here as well, the takeaway isn’t that there isn't a place for engagement, consultation and informing - there will be times when those approaches might be more suitable or even necessary based on the goals of your project. The aim of presenting this is simply to demonstrate the difference between these approaches and co-design and to simply to be clear about what co-design is and what it isn't.